No products in the cart.

The bill polearm was originally an agricultural tool, which, after a number of changes, became widely used in the military field. The main popularity fell on the 14th-17th centuries. It was most commonly used in England, but was also seen in France, Italy and America during the colonial period.

The history of the bill:

Bill came from the bill hook tool, which was used to prune the branches of fruit trees. The tool was important because it allowed to collect branches for the construction of houses, or rather to strengthen clay walls.

Being a

fairly popular everyday tool in the conditions of regular feudal conflicts, a

military variation of the billhook arose. During the war, ordinary villagers

and poor townspeople could not afford to equip themselves with expensive

weapons like halberds.

The

appearance of the combat version of the bill hook was caused by the cheapness

in manufacturing, since complex forging methods were not required, similar to

the halberd. That is, it was possible to make a bill weapon without using the

forge welding method by the blacksmith, with the exception of the spike, which

was not on all copies. Also, less iron was consumed, which in the medieval era

was very expensive, not to mention steel. The state also could not afford the

high costs of equipping the militia. It was in this context that the combat

version of Bill Hook was born.

But also

representatives of a richer segment of the population could order a more

expensive version of the bill, for greater reliability and, of course,

aesthetics.

Appearance:

Bill shaft

weapon had many variations in appearance, depending on which craftsman forged

the product. The simplest forms of combat bill hook have a beak-shaped blade.

More complex ones have 1 spike and are slightly more difficult to manufacture.

Since the spikes probably required the use of forge welding (it all depended on

the preference of the master). By type it can be attributed to glaives. The

length of the shaft was 120 cm, and the head was about 40 cm.

Also, this

type of glaive was divided into white and black:

White bill

was usually forged by a city gunsmith, who has more narrowly focused knowledge

and used higher-quality raw materials. Steel and iron for the city blacksmith

were made by separate craftsmen. A gunsmith, in the presence of a good one,

could forge a high-quality glaive and, if desired, a more aesthetic appearance.

Black bill

was made by village blacksmiths who acted as multidisciplinary specialists.

That is, unlike their urban colleagues, they had to make iron or more or less

carbon steel on their own. Starting from the stage of searching in rivers,

swamps and other places for iron compounds, which then needs to be turned into

ore.

This was

followed by the stage of processing and transformation into a pig iron with the

help of a bloomery. After that, the raw materials required partial recovery to

increase the carbon in the alloy and reduce the slag. Naturally, one village

blacksmith with conditional assistants who have basic knowledge of the

manufacture of raw materials most likely would not be able to observe the

quality of steel or iron that a city master would have.

Application and

effectiveness of the bill on the battlefield:

Glaive Bill

in the hands of a simple warrior (a former peasant) could be much more

effective during the battle. First of all, the variations of the military billhook

have a beak-shaped blade with a different level of bend, with which it was

possible to hook the enemy in the area of the articulation of the armor. The

beak could break through the chain mail when applying a sweeping slashing blow.

The spike on the head of some specimens could also be used in combat. The

pecking blow of the tip could be effective against both chain mail or plate

armor. Due to the long shaft, an enemy with a short weapon had less chances,

especially in a tight formation.

Theoretically,

under certain conditions, a detachment armed with such a subtype of glaive

could be successfully used against cavalry:

The success

of such a foot detachment could be caused by the critical smallness of the

enemy's cavalry, which did not allow during the battle to break the formation

and undermine the morale of the infantrymen. If there is a conditional meeting

of several horsemen and infantrymen with bills, the shaft weapon could really

manifest itself due to the ability to catch on the joints of armor and rings of

chain mail.

Also,

billmen can gain the upper hand under difficult terrain conditions, which will

not allow the cavalry to maneuver and hit the infantry in different directions.

Basically, of course, it will be a narrow space, for example, a break in the

wall. In such conditions, a small group of billmen with a low level of

organization will be able to resist cavalry.

In an open

area, warriors with glaives without a serious military organization will not be

able to resist cavalry without serious support from the allied cavalry and

cavalry. It will be enough for the cavalry to break through the first ranks to

reduce the defenses of the infantry. The only ones who could defeat the cavalry

were Swiss mercenaries and landsknechts due to high professionalism and the use

of firearms coupled with pikes and other melee weapons.

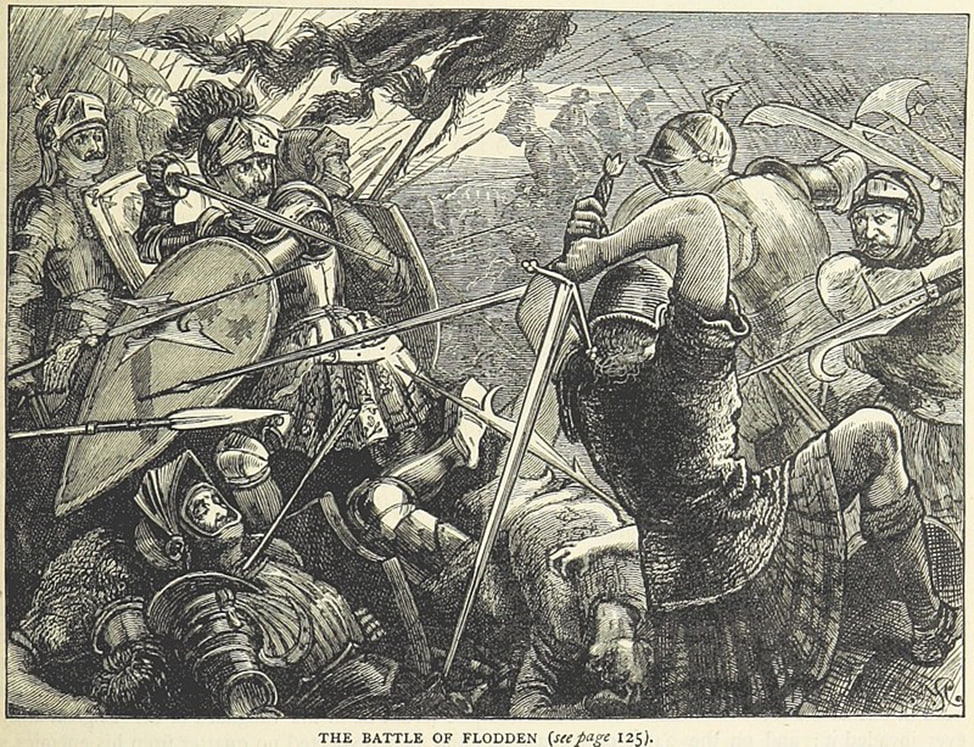

In terms of prevalence on the battlefield, the British Isles took the first place in popularity. In England at the beginning of the 16th century, a combination of bow and bill was used, while in other European countries the combination of arquebuses and spades was changed. The most famous use of the bill in battle was the Battle of Flodden in 1513.

About 20%

of the troops of the English kingdom were armed with this subtype of glaive.

During the Italian War of 1542 – 1546, the main shaft weapon of the British was

the bill. There the British defeated the Scottish pikemen relying on Billmen

and archers with the support of artillery.

The further fate of Bill:

By the end

of the 17th century, the bill was quite an outdated weapon, however, like most

other glaives. However, it was still used by English colonists in North

America. Thus, Bill Hook's agricultural tool turned out to be a fairly cheap,

but excellent weapon for battle. As a result, for the period of the 15th – 17th

century, the infantry troops of the English kingdom were supplied with bills.