No products in the cart.

The history of polearms has a long period of use in combat of battle axes. The Sumerians also used copper axes for battles. In the ancient era, axes were actively used by the Germans, Celts, Scythian horsemen and other peoples with a tribal system. In antiquity, first of all, copies of copper and bronze were distributed, then by the end of the era, blades of iron appeared.

In the period after the fall of the Roman Empire, the era of the Early Middle Ages began, which lasted from the 5th to the 11th century AD. During this period, battle axes on a long shaft appeared, which were actively used against warriors in chain mail. Axes were effective before the appearance of plate armor from knights in the 14th century.

Poleaxe as an answer to plate

armor:

During the

period of the spread of plate armor since the 14th century, there was a need to

improve cold weapons for new realities of battle for more effective use. As a

rule, the issue of solving problems was approached by creating hybrid types of

weapons or highly specialized instances, such as misericorde. The most striking

examples of hybrid shaft weapons are axes and halberds.

In our

case, we will consider in detail the poleaxe:

Poleaxe

appeared as a result of combining an axe with a hammer or bec de corbin and

having a faceted spike. The length together with the shaft averaged 150 – 230

cm. The blade length on average did not exceed 20 cm. The weapon was quite

versatile. They could crush armor, deliver chopping blows and stab a thorn in

the joint. The spike was attached separately on top of the axe with the help of

splints, which were tightened with a through rod. The splints provided

additional strength, reducing the likelihood of the shaft breaking during the

strike. The shaft closed with a splint allowed to reflect blows.

An exact

copy of the French poleaxe dating back to 1400 – 1450. The blade length is 15

cm.

Poleaxe was

used exclusively by knights and possibly their armed servants. Most of the

authentic copies had rich decoration, traces of etching. All this emphasized the

high status of the owner of this pole weapon.

Based on

numerous data, poleaxes were used by the knight cavalry during dismounting and

battle on foot. They were actively used by knights when it was necessary to

complete a task where mounted combat could be useless.

The Battle

of Aljubarrota. 1385 year

For

example, when storming the castle walls. A plate warrior with such a weapon in

his hands with a group of the same knights were a serious threat to the

defending side. From a blow with the blade of an axe with an average length of

15 cm, a shield or gambeson, in which ordinary infantrymen were usually

dressed, could not be saved. In the event of a collision with the same

dismounted knight cavalry, an equal battle would have turned out (assuming

approximately equal numbers of each side of the battle).

Tournament weapon and a

way to resolve legal disputes:

Poleaxes

were a mandatory part during jousting tournaments. So the famous French knight Jacques

de Lalaing at a tournament in 1445 in the city of Antwerp with his partner in

the duel Jean de Boniface broke 6 spears before taking up the poleaxes. Jacques

de Lalaing, with the help of poleaxe, was able to decide the outcome of the

duel in his favor by disabling the opponent with one blow. The same Frenchman,

during a tournament duel with the Englishman Thomas Kew in Flanders in 1447,

was wounded in the arm with a thorn. The spike of poleaxe pierced the gauntlet and went through, but

Jacques, having been wounded, threw his weapon, pushed his opponent to the

ground and became the winner. Surprisingly, after that, the hand healed, and

the hero of the jousting tournaments remained healthy.

They were also used during court fights when the feudal lords could not resolve disputes peacefully.

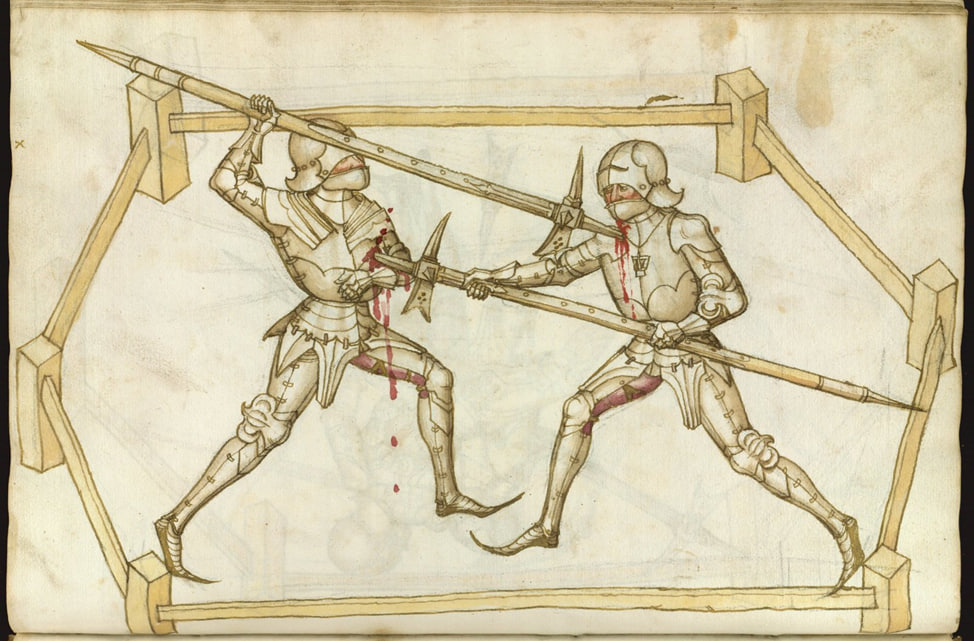

Trial by

combat, 1459. This drawing clearly shows that the thorn was struck in poorly

protected places, armpits and neck. Also, despite all the power of the weapon,

we see that the knights preferred to finish off with a thorn in the joint of

the armor. And blows with a blade or a hammer served to cause injuries (bruises

and fractures), which were supposed to disable the enemy. It is possible to

pierce a full plate armor with a blade, but it would take a lot of time within

the battle. But it was easier to crush a separate area on the armor with a

hammer and pierce it with a spike.

Error in definition the poleaxe:

Quite often on the web you can find publications where poleaxes include pole weapon with a hammer tip and bec de corbin with a spike. This statement is fundamentally incorrect, since the poleaxe consists of two root words “pole” and “axe". That is, if there is a hammer on the tip instead of an axe, it is no longer a poleaxe. In this case, the weapon should be attributed to the Lucerne hammer, which were used in the same era.

According

to terminological definitions, the Lucerne hammer cannot refer to poleaxe.

Also, you

should not look for authentic medieval names of weapons. Since one type of

conditional glaive could have several, or even dozens of names. Medieval

warriors were very pragmatic people and followed the principle of call it a

pot, the main thing is that it worked. The exact terminology of weapons appears

closer to the 19th century.

Also,

sometimes they note the similarity with a halberd, but this will not be

entirely correct, since according to the production system, the poleaxe was

more expensive and more massive in weight. And the halberd was cheaper and

longer than its opponent. The blade of the halberd was shorter compared to the poleaxe,

which made it possible to strike with the blade at one point without scattering

inertia throughout the enemy's armor. Plus, parallel to the blade of the axe,

the halberd almost always had bec de corbin, the poleaxe could have an

alternative as a hammer on the spine.

The decline of the era:

Poleaxe

went out of circulation by the end of the 16th century. The probable reasons

were the firearms infantry, which could resist dismounted knights. Accordingly,

the knight cavalry did not need to fight on foot due to the reduction of

advantages and there was no need for poleaxe. In general, this pole weapon was

effective on the battlefield and in tournament duels of feudal lords throughout

the late 14th and until the end of the 16th century.